This article provides a critical analysis of neurofeedback in ADHD as a therapeutic method, examining its mechanisms of action and the current state of research evidence. We explore how this non-pharmacological approach works, what the latest studies reveal about neurofeedback effectiveness, and where significant questions remain unanswered. Understanding both the potential and limitations of this treatment option helps in making informed decisions about ADHD management strategies.

Table of Contents

What Neurofeedback Actually Is

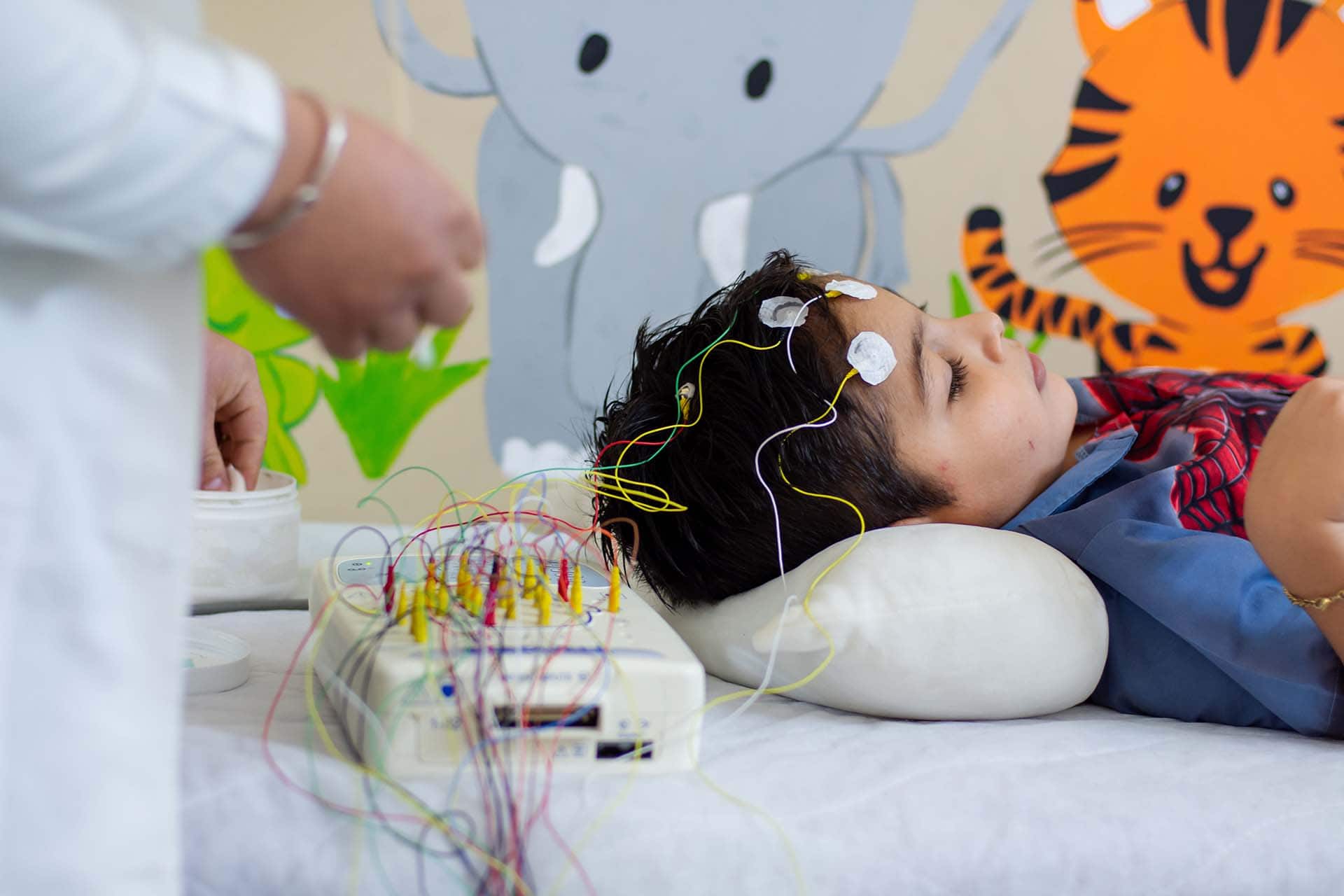

Neurofeedback represents a form of EEG biofeedback that allows individuals to observe their own brain activity in real time and learn to modify it through practice. During a typical clinical neurofeedback session, electrodes placed on the scalp measure electrical brain activity through electroencephalography. This information is then translated into visual or auditory feedback—perhaps a game that progresses when the desired brain patterns emerge, or sounds that change based on neural activity. The underlying principle draws from operant conditioning: behaviours that receive positive reinforcement tend to increase in frequency. Proponents argue that individuals with ADHD can learn to regulate their neural activity more effectively through repeated practice, potentially leading to symptom improvements that persist beyond the training period.

The Three Main Training Protocols

Three protocols have dominated neurofeedback in ADHD research and clinical practice:

- Theta/Beta Ratio (TBR) training: Aims to decrease slow theta waves whilst increasing faster beta waves, addressing the elevated theta/beta ratio often observed in ADHD

- Sensorimotor Rhythm (SMR) training: Focuses on enhancing 12-15 Hz activity over sensorimotor regions, originally developed for epilepsy treatment but later applied to hyperactivity

- Slow Cortical Potential (SCP) training: Teaches voluntary control over slow brain potential shifts, theoretically improving self-regulation of cortical excitability

Each protocol targets different aspects of brain function, and researchers continue debating which approach works best for specific ADHD presentations.

The Neurobiological Rationale

Research has established that ADHD involves alterations in brain function, particularly affecting networks responsible for attention control, impulse regulation, and executive functions. EEG studies frequently report distinctive patterns in ADHD populations, including increased slow-wave activity and reduced fast-wave activity in certain brain regions. These findings form the theoretical foundation for brain training interventions like neurofeedback. The prefrontal cortex and its connections to subcortical structures play crucial roles in these networks. When functioning optimally, these circuits enable us to maintain focus, suppress irrelevant information, and regulate responses. The hypothesis suggests that by training individuals to produce more typical brain wave patterns, we might enhance the functioning of these regulatory networks.

What the Research Evidence Shows

The scientific literature on neurofeedback effectiveness presents a complex picture. Numerous studies have investigated this approach, yet consensus remains elusive. Several meta-analyses have attempted to synthesise the available evidence, reaching somewhat different conclusions. Some systematic reviews report that neurofeedback produces effects comparable to stimulant medications when assessed by parents and teachers. These findings suggest potential value as one of several alternative forms of therapy for ADHD, particularly for families preferring non-pharmacological interventions. Long-term follow-up studies have documented sustained improvements months after training completion.

However, other analyses paint a more cautious picture. Studies employing rigorous control conditions—including sham neurofeedback where participants receive feedback unrelated to their actual brain activity—sometimes fail to demonstrate specific effects beyond those attributable to non-specific factors. The debate centres partly on what constitutes an appropriate control condition for ADHD treatment research. Recent network meta-analyses comparing different interventions have positioned neurofeedback within the broader landscape of ADHD management. These studies suggest that whilst neurofeedback shows promise, the evidence doesn’t yet establish it as superior to other established approaches. Questions persist about which patients benefit most and optimal training parameters. This questions is addressed in research together with efforts which protocols should best be used during neurofeedback training.

Practical Considerations for ADHD Treatment

For families considering neurofeedback, several practical factors merit attention. Treatment typically requires 10-20 sessions, each lasting approximately 45 minutes. This represents a substantial time commitment compared to daily medication. Costs vary considerably, but often aren’t covered by insurance, making accessibility a significant concern. Not everyone responds equally to neurofeedback training. Some individuals show dramatic improvements, others experience modest benefits, and a proportion notice no change. Predicting who will benefit remains challenging, though research into personalised protocols shows promise. Factors such as motivation, age, ADHD symptom severity, and the presence of co-occurring conditions may all influence outcomes.

The training itself demands active participation and sustained effort. Unlike taking medication, this behavioural training approach requires individuals to engage repeatedly with the learning process. This active involvement appeals to some people but proves burdensome for others, particularly children who may struggle with the attention demands of training sessions. Importantly, however, unlike the effects of medications, neurofeedback effects sustain making them effective tools the patients learn to apply in daily life.

Treating ADHD in Adults

Whilst most research has focused on children, interest in treating ADHD in adults through neurofeedback has grown considerably. Adults with ADHD often prefer non-pharmacological treatment options due to concerns about medication side effects or interactions with other treatments. The cognitive demands of neurofeedback training may actually suit adults better than children, as adults typically bring greater motivation and metacognitive awareness to the learning process. However, the evidence base for treating ADHD in adults remains more limited than for paediatric populations. The few existing studies suggest similar patterns to those observed in children—some participants benefit substantially, whilst results for others prove disappointing. Adults seeking neurofeedback should understand they’re accessing a treatment with promising but not yet definitive evidence.

Current Research Directions

Contemporary investigations are exploring several promising directions. Dr. Christian Beste’s work at TU Dresden has contributed to understanding the neurophysiological mechanisms underlying cognitive control processes, knowledge that informs the development of more targeted neurofeedback protocols. Researchers are increasingly examining whether training effects depend on actual learning to regulate brain activity, or whether other mechanisms account for improvements. Combined approaches integrating neurofeedback with other interventions—such as cognitive training or behavioural therapy—represent another avenue of investigation for improving ADHD symptoms through non-medication approaches. In the same manner, also the question which protocols should best be used during neurofeedback training is a major aspect of research in terms of personalized medicine.

Making Informed Decisions

Families and individuals considering neurofeedback benefit from understanding both its potential and limitations. This approach offers a non-pharmacological option that some find appealing, and evidence suggests it can produce meaningful improvements for certain individuals. The effects, when they occur, may persist after training concludes—an advantage over medications requiring ongoing administration. However, the evidence doesn’t yet support neurofeedback as a first-line ADHD therapy superior to established interventions. It requires substantial time and financial investment, and response rates vary considerably. Research groups such as Christian Beste’s continue working to clarify which patients benefit most and to optimise training protocols, but definitive answers remain elusive.

Those pursuing neurofeedback should seek practitioners with proper training and certification, ideally those who conduct baseline assessments and monitor progress objectively. Realistic expectations prove essential—neurofeedback rarely eliminates attention deficit hyperactivity disorder symptoms entirely, but may reduce their severity or help individuals develop better self-regulation strategies. As with any intervention, a comprehensive approach addressing multiple aspects of functioning typically yields the best outcomes.